I nice trick I learned a while ago that is worth sharing: calculating pi the unix way (you know, on the command line, with pipes, as god intended).

I would like to give credit to the original source of this command, but I just couldn't find it. It was some of those "shell one-liners" you see on hacker news five times a day, except I didn't know half of them. The most interesting was a semi-cryptic command line with a pretentious comment besides it:

# calculates pi the unix way

I remember as if it was today how puzzled I was by that line. As I said, I didn't know much of the incantations on that list, but this was by far the most magical. The line goes like this:

$ seq -f '4/%g' 1 2 9999 | paste -sd-+ | bc -l

If you like a challenge (as I do), try to figure it out by yourself. A shell and the man pages are your best friends.

seq

If shell (or python) wasn't your first programming language, you were probably surprised by the way loops are done. It usually goes like this:

$ for x in 1 2 3 4 5; do echo "$x"; done

1

2

3

4

5

If you have a little experience with shell, you probably learned there is a more idiomatic way of doing this using the seq command and some shell voodoo:

$ for x in $(seq 1 5); do echo "$x"; done

And if you were truly initiated on the dark arts of bash programming, you probably know this is functionally equivalent to this:

$ for x in {1..5}; do echo "$x"; done

I won't explain how shell command substitution works, suffice to say seq is a nice utility to generate sequences (get it?) of numbers. From the first lines of the man page:

$ man seq | grep -A 3 SYNOPSIS

SYNOPSIS

seq [OPTION]... LAST

seq [OPTION]... FIRST LAST

seq [OPTION]... FIRST INCREMENT LAST

So the main part of the first command on the pipe is no magic: we are generating numbers from 1 to 9999 with a step of 2:

$ echo $(seq 1 2 9999 | head -5)

1 3 5 7 9

There is a useful option to this command to control how the value is output:

$ seq -f '%02g' 1 3 10

01

04

07

10

Programmers familiar with c will recognize the printf format string. Moving down the pipe...

paste

There are some commands that do something so simple they seem almost useless:

$ whatis -l paste

paste (1) - merge lines of files

paste (1p) - merge corresponding or subsequent lines of files

Nothing really interesting here, right?

$ paste <(seq 1 3) <(seq 4 6)

1 4

2 5

3 6

$ seq 1 6 | paste - -

1 2

3 4

5 6

Well, that is interesting. What if we play with the other options?

$ paste -sd, <(seq 1 3) <(seq 4 6)

1,2,3

4,5,6

$ seq 1 6 | paste -sd,

1,2,3,4,5,6

This simple command is starting to show complex behavior. Maybe there is something interesting in those old unix books after all... Wait:

$ seq 1 6 | paste -sd+

1+2+3+4+5+6

Nice, a mathematical expression. If only we had some way of interpreting it...

bc

There are people who say: the python/ruby interpreter is my calculator. To that I say: screw that!

$ bc -ql

1 + 2 + 3

6

10 / 12

.83333333333333333333

scale = 80

10 / 12

.8333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333333\

3333333333333

Do you see that `\` character? It's almost as if it was meant to be used on a shell...

$ seq 1 6 | paste -sd+ | bc -l

21

Interlude: Gregory-Leibniz

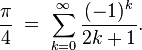

There are many ways of calculating π. You can find many of them on its wikipedia page. One of them is named after two mathematicians, James Gregory and Gottfried Leibniz, goes like this (again from wikipedia):

This is an infinite series with a simple pattern, which I'm sure you can identify (you weren't sleeping on those calculus classes, were you?). Just in case you can't (and because it is a pretty equation), here it is:

Back in unix-land

So here is the challenge: how can we generate and evaluate the terms of this series? Generating each term, without the sign, can be done easily with seq and a format string:

$ seq -f '1/%g' 1 2 9

1/1

1/3

1/5

1/7

1/9

Remember our useful-where-you-never-imagined friend paste?

$ seq -f '1/%g' 1 2 9 | paste -sd-+

1/1-1/3+1/5-1/7+1/9

This may take some time to understand, it's ok. Read those man pages! But once you understand, the only thing left is to evaluate the expression:

$ seq -f '1/%g' 1 2 9 | paste -sd-+ | bc -l

.83492063492063492064

Hmm, not much π-like, is it? Right, this is π/4. Ok, we can rearrange the terms a bit to fit our tools (that is the essential hacker skill). Lets move the denominator on the right side to the numerator on the left.

$ seq -f '4/%g' 1 2 9 | paste -sd-+ | bc -l

3.33968253968253968254

That's more like it! As any infinite series approximation, we can increase the number of terms to increase accuracy:

$ seq -f '4/%g' 1 2 9999 | paste -sd-+ | bc -l

3.14139265359179323814

Now just for the heck of it:

$ seq -f '4/%g' 1 2 999999 | paste -sd-+ | bc -l

3.14159065358979323855

And there you have it. Enjoy your unix π.

Thursday, December 11, 2014

Wednesday, December 10, 2014

pip --extra-index

This is a tale of debugging. That fine art of digging the darkest corners of a computer system to solve whatever problem is haunting it. This particular story is about python's package manager, pip.

Where I work, we have a server where we store all python packages used in development and production. A package "cache" or "proxy". The idea is similar to a http proxy: we don't have to hit PyPi for each package query and install. That saves time, as local connections are much faster, both regarding latency and throughput, and bandwidth, as no packet has to leave our lan.

One day, all of a sudden, our testing and production servers started taking a long time to run a simple package update. And when I say "a long time", I mean taking more than ten minutes to run a simple `pip install --update` with roughly fifty packages on a requirements.txt file. That is a ridiculously long time. That would be crazy slow even if we were hitting the wan, but on a lan, that is just absurd. So, clearly, something fishy was going on.

Debugging begins

Step one when debugging an issue: figure out what changed. I thought long and hard (harder than longer, I must admit) about it, but couldn't think of anything I or anyone else had changed on these machines recently. So I advanced to step two: getting a small, reproducible test.

In this case, the test can be reduced to a simple command line execution:

$ pip install -Ur requirements.txt

This is a standard pip requirements file, with the standard options to prefer our internal server over the official PyPi server:

$ head -2 requirements.txt

--index-url=http://pypi.example.com/simple/

--extra-index-url=http://pypi.python.org/simple/

Here and in the next examples, I'll substitute the real domains for our servers for fake ones. Anyway, running that one simple command was all that was needed to test the strange behavior. On my personal development machine, that took quite a while:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m41.280s

user 0m3.557s

sys 0m0.100s

Even more interestingly, this was way less time than we were seeing on the servers:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 13m19.752s

user 0m1.031s

sys 0m0.184s

On the server

The three main servers affected by this issue (the ones I spend most time in) were our buildbot (i.e. continuous integration), staging and production servers. I decided the first test would be on the buildbot server, as it is the same server where the packages are hosted. That way, I can exclude many external factors that could be affecting the traffic.

So I fired my favorite tool: the amazing strace. If you don't know it, stop everything and go take a look at `strace(1)`. Since I know most people won't, here's a quick introduction: strace execve(2)'s your command, but sets up hooks to display every system call it executes, along with arguments, return values and everything. It is an amazing tool to have an overall idea of what a process is doing. If you are root (and have CAP_SYS_TRACE), you can even attach to a running process, which is an amazing way to debug a process that starts running wild.

Using it to run the command:

$ strace -r -o strace.txt pip install -Ur requirement.txt

The arguments here are `-o strace.txt` to redirect output to a file and the super useful `-r` to output the relative time between each system call, which is perfect to identify the exact system calls slowing down the execution of the command.

After the execution was done, looking at the output, I found the culprit. Here is a sample of the log:

$ grep -m 1 -B 5 close strace.txt

0.000138 socket(PF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 4

0.000115 fcntl(4, F_GETFL) = 0x2 (flags O_RDWR)

0.000092 fcntl(4, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

0.000089 connect(4, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(80), sin_addr=inet_addr("23.235.39.223")}, 16) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

0.000128 poll([{fd=4, events=POLLOUT}], 1, 15000) = 0 (Timeout)

15.014733 close(4)

From this point, my analysis had some flaws that delayed the final conclusion. I will explain my line of thought as it happened, maybe you'll find the mistakes before I get to them. So, as can be seen in the output, a socket is opened to communicate with another server, which is normal behavior for pip, but then closing it takes around fifteen seconds. Hmm, that is really odd.

So I ran the command again and, while it was blocked waiting, I used another useful command to list the open file descriptors of the process:

$ lsof -p $(pgrep pip) | tail -2

pip 19928 django 3u IPv4 8064331 0t0 TCP

pypi.example.com:38804->pypi.example.com:http (CLOSE_WAIT)

pip 19928 django 4u IPv4 8064359 0t0 TCP

pypi.example.com:30470->199.27.76.223:http (SYN_SENT)

Here we have two open sockets. One of them is in the CLOSE_WAIT state. Anyone who's ever done socket programming knows this dreaded state, where the local socket is closed but the remote end doesn't send the FIN packet to terminate the connection. A few minutes of tcpdump later, I was convinced that was the problem: something was preventing the connection from ending and each operation was waiting for the timeout to close the socket. That would explain why closing the socket took so long.

The mistakes

At this point, I realised my first mistake. If you take a look at the strace output again, the remote end of the socket is *not* our server. Take a look at the remote address (the `sin_addr` parameter to the `socket` call): 23.235.39.223 is not the ip address of our server, and taking a look at the rest of the output showed that the address changed over time.

There should be no other servers involved, since we explicitly told pip to fetch packages from our own server. So I thought: what other server could be involved here? So I took a guess:

$ dig pypi.python.org | grep -A 2 'ANSWER SECTION'

;; ANSWER SECTION:

pypi.python.org. 52156 IN CNAME python.map.fastly.net.

python.map.fastly.net. 30 IN A 23.235.46.223

Damn... Wait!

$ dig pypi.python.org | grep -A 2 'ANSWER SECTION'

;; ANSWER SECTION:

pypi.python.org. 3575 IN CNAME python.map.fastly.net.

python.map.fastly.net. 7 IN A 23.235.39.223

Bingo! So it was a connection to one of PyPi's servers. I went back to the strace output and realised my second mistake. If you read strace's man page section for the `-r` option carefully, the delta shown before each line is not the time each syscall took, but the time between that syscall and the last. So the operation that was getting stuck was not `close`, but the previous, `epoll`.

In hindsight, it is obvious. You can see the indication that the call timed out. You can even see the timeout is one of the parameters. And so the mystery was solved. By some unknown reason, pip was trying to make a connection to PyPi after checking our server. Since we don't allow that, the operation hang around until the timeout was reached. One final test confirmed our suspicion:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m42.981s

user 0m3.720s

sys 0m0.070s

$ sed -ie 's/^--extra-index/#&/' requirements.txt

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m1.049s

user 0m0.853s

sys 0m0.057s

Removing the extra index option eliminated the issue (and gave us a ~42x speed up, something you don't see everyday).

Conclusion

So, what do we take out of this (unexpectedly long) story? If you are using a local package server, don't use `--extra-index`. I have no idea why pip was trying to contact the extra index after finding the package on our server. The only reason I can think of is it is trying to find a newer version of the package, but even then, most of our requirements are fixed, i.e. they have '==${some_version}' appended.

Even on my development machine, where pip can reach the remote server, it is worth it to remove the option. The time it takes just to reach the server for each package, even just to receive a "package up-to-date" message, slows down the operation considerably:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m46.816s

user 0m3.853s

sys 0m0.130s

$ sed -ie 's/^--extra-index/#&/' requirements.txt

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m1.125s

user 0m0.947s

sys 0m0.053s

Coda

Thank you for making it this far. I hope this story was entertaining and hopefully it taught you a thing or two about investigation, debugging and problem solving. Take the time to learn the basic tools: ps, lsof, tcpdump, strace. I assure you they will be really useful when you encounter this type of situation.

Where I work, we have a server where we store all python packages used in development and production. A package "cache" or "proxy". The idea is similar to a http proxy: we don't have to hit PyPi for each package query and install. That saves time, as local connections are much faster, both regarding latency and throughput, and bandwidth, as no packet has to leave our lan.

One day, all of a sudden, our testing and production servers started taking a long time to run a simple package update. And when I say "a long time", I mean taking more than ten minutes to run a simple `pip install --update` with roughly fifty packages on a requirements.txt file. That is a ridiculously long time. That would be crazy slow even if we were hitting the wan, but on a lan, that is just absurd. So, clearly, something fishy was going on.

Debugging begins

Step one when debugging an issue: figure out what changed. I thought long and hard (harder than longer, I must admit) about it, but couldn't think of anything I or anyone else had changed on these machines recently. So I advanced to step two: getting a small, reproducible test.

In this case, the test can be reduced to a simple command line execution:

$ pip install -Ur requirements.txt

This is a standard pip requirements file, with the standard options to prefer our internal server over the official PyPi server:

$ head -2 requirements.txt

--index-url=http://pypi.example.com/simple/

--extra-index-url=http://pypi.python.org/simple/

Here and in the next examples, I'll substitute the real domains for our servers for fake ones. Anyway, running that one simple command was all that was needed to test the strange behavior. On my personal development machine, that took quite a while:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m41.280s

user 0m3.557s

sys 0m0.100s

Even more interestingly, this was way less time than we were seeing on the servers:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 13m19.752s

user 0m1.031s

sys 0m0.184s

On the server

The three main servers affected by this issue (the ones I spend most time in) were our buildbot (i.e. continuous integration), staging and production servers. I decided the first test would be on the buildbot server, as it is the same server where the packages are hosted. That way, I can exclude many external factors that could be affecting the traffic.

So I fired my favorite tool: the amazing strace. If you don't know it, stop everything and go take a look at `strace(1)`. Since I know most people won't, here's a quick introduction: strace execve(2)'s your command, but sets up hooks to display every system call it executes, along with arguments, return values and everything. It is an amazing tool to have an overall idea of what a process is doing. If you are root (and have CAP_SYS_TRACE), you can even attach to a running process, which is an amazing way to debug a process that starts running wild.

Using it to run the command:

$ strace -r -o strace.txt pip install -Ur requirement.txt

The arguments here are `-o strace.txt` to redirect output to a file and the super useful `-r` to output the relative time between each system call, which is perfect to identify the exact system calls slowing down the execution of the command.

After the execution was done, looking at the output, I found the culprit. Here is a sample of the log:

$ grep -m 1 -B 5 close strace.txt

0.000138 socket(PF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, IPPROTO_TCP) = 4

0.000115 fcntl(4, F_GETFL) = 0x2 (flags O_RDWR)

0.000092 fcntl(4, F_SETFL, O_RDWR|O_NONBLOCK) = 0

0.000089 connect(4, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(80), sin_addr=inet_addr("23.235.39.223")}, 16) = -1 EINPROGRESS (Operation now in progress)

0.000128 poll([{fd=4, events=POLLOUT}], 1, 15000) = 0 (Timeout)

15.014733 close(4)

From this point, my analysis had some flaws that delayed the final conclusion. I will explain my line of thought as it happened, maybe you'll find the mistakes before I get to them. So, as can be seen in the output, a socket is opened to communicate with another server, which is normal behavior for pip, but then closing it takes around fifteen seconds. Hmm, that is really odd.

So I ran the command again and, while it was blocked waiting, I used another useful command to list the open file descriptors of the process:

$ lsof -p $(pgrep pip) | tail -2

pip 19928 django 3u IPv4 8064331 0t0 TCP

pypi.example.com:38804->pypi.example.com:http (CLOSE_WAIT)

pip 19928 django 4u IPv4 8064359 0t0 TCP

pypi.example.com:30470->199.27.76.223:http (SYN_SENT)

Here we have two open sockets. One of them is in the CLOSE_WAIT state. Anyone who's ever done socket programming knows this dreaded state, where the local socket is closed but the remote end doesn't send the FIN packet to terminate the connection. A few minutes of tcpdump later, I was convinced that was the problem: something was preventing the connection from ending and each operation was waiting for the timeout to close the socket. That would explain why closing the socket took so long.

The mistakes

At this point, I realised my first mistake. If you take a look at the strace output again, the remote end of the socket is *not* our server. Take a look at the remote address (the `sin_addr` parameter to the `socket` call): 23.235.39.223 is not the ip address of our server, and taking a look at the rest of the output showed that the address changed over time.

There should be no other servers involved, since we explicitly told pip to fetch packages from our own server. So I thought: what other server could be involved here? So I took a guess:

$ dig pypi.python.org | grep -A 2 'ANSWER SECTION'

;; ANSWER SECTION:

pypi.python.org. 52156 IN CNAME python.map.fastly.net.

python.map.fastly.net. 30 IN A 23.235.46.223

Damn... Wait!

$ dig pypi.python.org | grep -A 2 'ANSWER SECTION'

;; ANSWER SECTION:

pypi.python.org. 3575 IN CNAME python.map.fastly.net.

python.map.fastly.net. 7 IN A 23.235.39.223

Bingo! So it was a connection to one of PyPi's servers. I went back to the strace output and realised my second mistake. If you read strace's man page section for the `-r` option carefully, the delta shown before each line is not the time each syscall took, but the time between that syscall and the last. So the operation that was getting stuck was not `close`, but the previous, `epoll`.

In hindsight, it is obvious. You can see the indication that the call timed out. You can even see the timeout is one of the parameters. And so the mystery was solved. By some unknown reason, pip was trying to make a connection to PyPi after checking our server. Since we don't allow that, the operation hang around until the timeout was reached. One final test confirmed our suspicion:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m42.981s

user 0m3.720s

sys 0m0.070s

$ sed -ie 's/^--extra-index/#&/' requirements.txt

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m1.049s

user 0m0.853s

sys 0m0.057s

Removing the extra index option eliminated the issue (and gave us a ~42x speed up, something you don't see everyday).

Conclusion

So, what do we take out of this (unexpectedly long) story? If you are using a local package server, don't use `--extra-index`. I have no idea why pip was trying to contact the extra index after finding the package on our server. The only reason I can think of is it is trying to find a newer version of the package, but even then, most of our requirements are fixed, i.e. they have '==${some_version}' appended.

Even on my development machine, where pip can reach the remote server, it is worth it to remove the option. The time it takes just to reach the server for each package, even just to receive a "package up-to-date" message, slows down the operation considerably:

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m46.816s

user 0m3.853s

sys 0m0.130s

$ sed -ie 's/^--extra-index/#&/' requirements.txt

$ time pip install -Ur requirement.txt &> /dev/null

real 0m1.125s

user 0m0.947s

sys 0m0.053s

Coda

Thank you for making it this far. I hope this story was entertaining and hopefully it taught you a thing or two about investigation, debugging and problem solving. Take the time to learn the basic tools: ps, lsof, tcpdump, strace. I assure you they will be really useful when you encounter this type of situation.

Labels:

debugging,

grep,

linux,

lsof,

man,

pip,

programming,

python,

socket,

strace,

unix,

webserver

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)